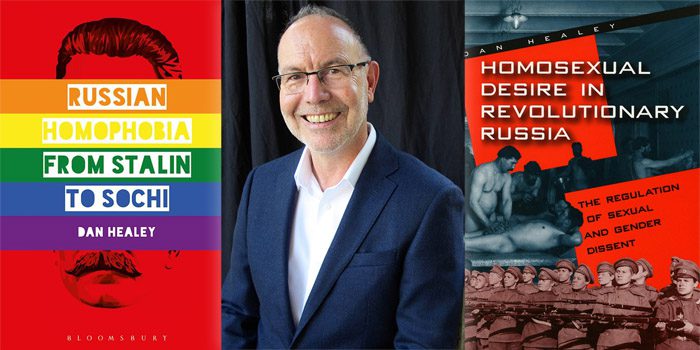

By Antony Sπyros.British historian Dan Healey on the evolution of attitudes towards homosexuality, the likelihood of a global right turn and the prospects for Russian queers

In the summer of 2022, at the height of the Russian-Ukrainian war and on the eve of the beginning of the mass repressions of the Kremlin regime against LGBTQ people in Russia, a new revised and updated translation of Professor Dan Healey’s book Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent was published in Russian (under the title of «Другая история. Социально-гендерное диссидентство в революционной России»). This British historian became one of the first and most profound researchers of the Soviet queer community.

A year after the release of the book, Professor Healey gave an exclusive interview to the Parni PLUS portal. We talked about the changes in the historian’s own views on homosexuality over the years, the ups and downs of the world history, and the future of queer Russians after the end of the Putin’s war.

Dr. Healey, why did you choose LGBT people in Russia as the object of your research?

My interest grew from two quite separate interests I developed as a teenager, living in a small town in eastern Ontario, Canada. The first was that I came out as gay in 1973, in response to reading some of the new literature on gay liberation. My interest in the ideas, politics, and future of gay and lesbian liberation expanded as I grew older and discovered that there was a surprisingly long history of thought and action to improve the condition of queer people. I wanted to know more about the thinkers and activists who made being queer livable and who envisioned a happier queer existence.

The second interest was in the culture, language, and history of Russia. In 1974 my high school organized a tour of the USSR and I travelled with 30 students and parents from Canada to Helsinki, Leningrad, and Moscow on a two-week Intourist tour. We saw all the “usual menu” of Intourist sights – Kremlin, ballet, Hermitage, Red Square – and it was very exciting. I read Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago that year too; a very different perspective on the USSR. I decided to study Russian language and literature in my undergraduate degree at U of Toronto (1976-81). Eventually, it seemed necessary to combine the two interests – especially as there was almost no information about LGBT in the Soviet Union at that time. In the late 1980s I returned to do post-graduate study, as the Soviet Union was changing, and it became possible to imagine researching the LGBT history of the USSR and Russia.

Why is it important for the community to know its history? And what practical benefit can your research give to LGBT people in Russia?

I think knowledge of how LGBT people have managed the dilemmas of queerness in the past is a very powerful thing to have, and I believe strongly that all young people should have access to this knowledge. For the individual it is an important tool for building a happier and more viable self. For the community historical knowledge helps to consolidate a common identity and a sense of shared perspectives. LGBT people are extremely diverse, so it is important to understand, as a community, the kinds of oppression and possibilities that bring us together. History can contribute to that. The Russian “specificities” really make having a history that much more important: it can feel like an overwhelmingly immense, conservative, unchangeable society, and to understand your history can reassure you that change is possible, and that change spreads fast across great distances in Russia.

Has your attitude towards homosexuality changed over the course of your life?

Inevitably, it has. First there has been an enormous intellectual shift from the “gay liberation” I read about in the early 1970s to the queer theory and LGBTQ studies of the present day. I have not always paid strict attention to these shifts and sometimes I feel like a visitor from the past still hanging on to “gay lib” when the world around me has changed. But other times I recognize that my understanding of queerness is richer, more diverse, and more experiential than it was when I was 17, 18, 19. Of course, as a man in my 60s, for obvious reasons, my experience of same-sex attraction and intimacy is entirely different from what it was in my teens and twenties. In my life sexuality has been a provoker of crises and ruptures, an exciting adventure, a bad decision-maker, a magnet drawing me to other men, a destructive raging fire and a perfect barbecue with a long-lasting coals. I think that this learning and changing is an immense lifetime journey that would take a book to explain. It’s one of the reasons why I enjoy reading queer memoir now, to see how others have managed this wild ride.

Does the economic collapse of the state contribute to the growth of conservative sentiments, including homophobia? And if so, how do countries like Argentina manage to maintain a great level of tolerance in the society even in times of the deepest crisis?

I’m not really an economist or political scientist, so my answer to this question is based on historical examples and contemporary observation. Historically, political homophobia has accompanied economic collapse – think of Nazi Germany – but the causal link is not that strong. Why did political homophobia in the West rise during the early Cold War when prosperity was taking off? I don’t know very much about Argentinian politics, but it’s clear that most Spanish-speaking societies have evolved into fairly polarized entities with a conservative right that favours ‘traditional values’ and a leftist tendency that favours freedom to love. After a time these political agendas get ‘baked in’ to each side’s programme and I think they remain ‘in reserve’ to draw upon in times of crisis.

The intellectual movement of the New Right, the popularity of right-wing populists like Marie Le Pen in France, Viktor Orban in Hungary or Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil – are these the first flashes of a global right turn of humanity or a temporary and surmountable crisis of liberal democracy?

You’re right to emphasise the possibility of a turning point. People who believe in liberal democracy have to wake up every morning and go to work to defend liberal values, every day: they are never safe, ever. The truth is they never were – they have to be defended, argued for, embedded, explained, and taught, in every successive generation. What is clear from the global movement of populists (if you can even speak of such a thing – I’m not persuaded) is that they vary tremendously in competence as rulers, in intelligence, in ruthlessness, and this can be a starting point for fighting them. And they work within existing political frameworks that are never entirely without cracks and weaknesses. They haven’t yet actually joined forces in a new Axis of Evil so I would not prematurely lump them together: they are more like rats in a sack, just as likely to eat each other alive.

After the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, the Putin regime has often been defined as far-right, imperial and even fascist. Is this true from your point of view? And do such regimes always rely on homophobia, or is there still no direct correspondence between the right-wing ideology and LGBT oppression?

Again, I’m no political scientist, and what I choose to label Putin’s style of rule is hardly going to bring down his regime. It’s obviously imperialistic in a classical 19th-century sense, and that’s a dangerous trend with horrific consequences for Ukraine. And for Russia’s relations with its neighbours for the next century. I would even venture to say the Russia has adopted a totalitarianism-light formula: it has purged all non-conformist media and civil society, with LGBTQ it has adopted a scapegoat to persecute and distract the population from its own suffering, and extra-judicial killing is a routine tool for Putin. But that’s just my hot take. I think sometimes that squabbles over definitions are not as helpful as pragmatic action to save people from Russia’s violence in Ukraine.

For the first decade and a half of its history, the USSR was one of the few places on the planet where LGBT people were not in danger, at least not due to their nature. The flywheel of political repressions unfolded, entire classes of society were destroyed, but in this aspect the Soviet was definitely ahead of its time. In your opinion, what is this connected with and why by the mid-1930s the country returned to the imperial conservatism, albeit in a new ideological shell?

There are two competing traditions in European socialism when it comes to LGBTQ politics, and I argue that the more positive, sodomy-decriminalizing ‘early Bolshevik’ policy of the pre-Stalin years of Soviet Rule constitutes one tradition. The other tradition is embodied in the Stalinist homophobic turn of the 1930s you mention. All later socialist regimes, building on the legacy of Moscow’s socialism reckoned with these two traditions and tried to navigate the contradictions. The first problem with the two competing European socialist traditions regarding queers is that there was very little space in the socialist movement for queers to express themselves. In the early Soviet republic there were ordinary queer people who assumed that decriminalization of sodomy meant the sexual revolution included them, but there was no public development of, or commentary on, this idea from queer or straight Soviet thinkers or political actors. It proved very easy to flip to the other revolutionary socialist tradition – the one where queers are a pathology that revolutionary values will eradicate.

Despite the return of criminal punishment for sodomy, the Soviet Union remained a relatively tolerant state throughout the 20th century. After all, a disproportionately small number of people were punished under this article, the punishment itself was quite mild by the standards of a totalitarian state. While in developed democracies gays were lobotomized, in the USSR they received a maximum of 5 years in prison, and this affected a few. Is this due to the specifics of the Soviet regime, or is homophobia not generally characteristic of Russian statehood?

I think the answer lies not in some kind of essentialised ‘immunity’ from homophobia in the Russian DNA, but in a more complex combination of cultural, scientific, policing, legal, and political traditions that affected the phenomena you point to. Rough comparisons across very different contexts seldom survive closer scrutiny. Take medicine and lobotomy, for example. Psychiatry was relatively under-resourced in the post-1945 Soviet Union, and it was overwhelmed with what we could call ‘real problems’ stemming from the trauma of war and state terror. It had little time or money for tinkering with cures for queers with expensive and risky lobotomies – which Soviet psychiatric leaders rejected on principled grounds for all kinds of mental illnesses, not just queer sexualities. Remember they were morally comfortable with using drugs to kill the libido of lesbians, or subdue the will of political dissidents. To take the example of police action against queers, yes, Soviet policing was apparently less systematically homophobic than what historians see in some Western jurisdictions – but there was more economic and social freedom too. And what kind of treatment could one of the hundreds of men who were sent to Soviet colonies and camps expect over the ‘short’ five years of their sentences? The fate of the ‘degraded ones’ in Soviet camps was notorious. By comparison a British queer would get a couple of years in an actual prison for gross indecency and a US queer’s sentence would be similarly short, depending on the state and the judge. And these would be served in Western prisons with bad conditions but at least better than poorer Soviet facilities. So, I would be more careful about such comparisons – they only really help Russian nationalists.

Russia, apparently, is on the brink of a new round of history: collapse of the totalitarian system which is far from being as effective as even the Soviet one, economic and legal chaos, attempts at new democratization. In your opinion, what mistakes from the 1990s should the West take into account and how to make gay revolution in Russia finally happen?

I am very sorry to say this, but I don’t think the West is going to be interested in making any kind of ‘revolutions’ in Russia, in contrast to the 1990s. When the ‘new round of history’ emerges, the West is going to focus on the reconstruction of Ukraine after the terrorist Russian state’s brutal destruction of its neighbour’s infrastructure, industry, agriculture, homes, schools, hospitals, museums, historical monuments, and so on. The impetus for rehabilitating Russia isn’t going to come from Washington or Brussels. Probably it will come from China. That choice already seems to have been made by Putin and an entire generation of Russian leaders and opinion-makers.

You have properly studied the experience of LGBT survival in the totalitarian Russia of the past. Now, new generations, who are unaware of this experience, found themselves in a similar situation. How can a gay, lesbian or non-binary person survive in Putin’s Russia in 2022? What can increase the chances of surviving this period?

It’s hard for me to imagine what might be possible under Putin’s regime after the 9 November 2022 ‘Decree on the Confirmation of Fundamental Principles of State Policy to Preserve and Strengthen Traditional Russian Spiritual-moral Values. ’This decree makes ‘traditional values’ a state security priority and forces every aspect of the state’s operations through the filter of promotion of heteronormativity. There’s nowhere to hide from this kind of state, once the decree’s orders are fully implemented. I hope that it won’t come to that. And I think that digital media may give possibilities for staying safe ‘under the radar’ of state surveillance. I’m also aware that many queer people have opted for emigration as a rational response to this kind of psychological and political terror. It is a sad reality that huge reserves of creativity and courage are being drained from Russia, driven away by the state’s turn against its own citizens.